Harvard Study: Mechanical Stimulation Leads to Muscle Repair

A new research to come out of Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University and the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) suggests that mechanical stimulation will one day be able to help with muscle repair.

The study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. recently, shows skeletal muscle regeneration can be promoted in this manner. It could improve upon the current practices, or perhaps replace them entirely in the future if the method is adopted successfully.

“The results of our new study demonstrate how direct physical and mechanical intervention can impact biological processes and can potentially be exploited to improve clinical outcomes,” says David Mooney, a member of the team that is carrying out the study.

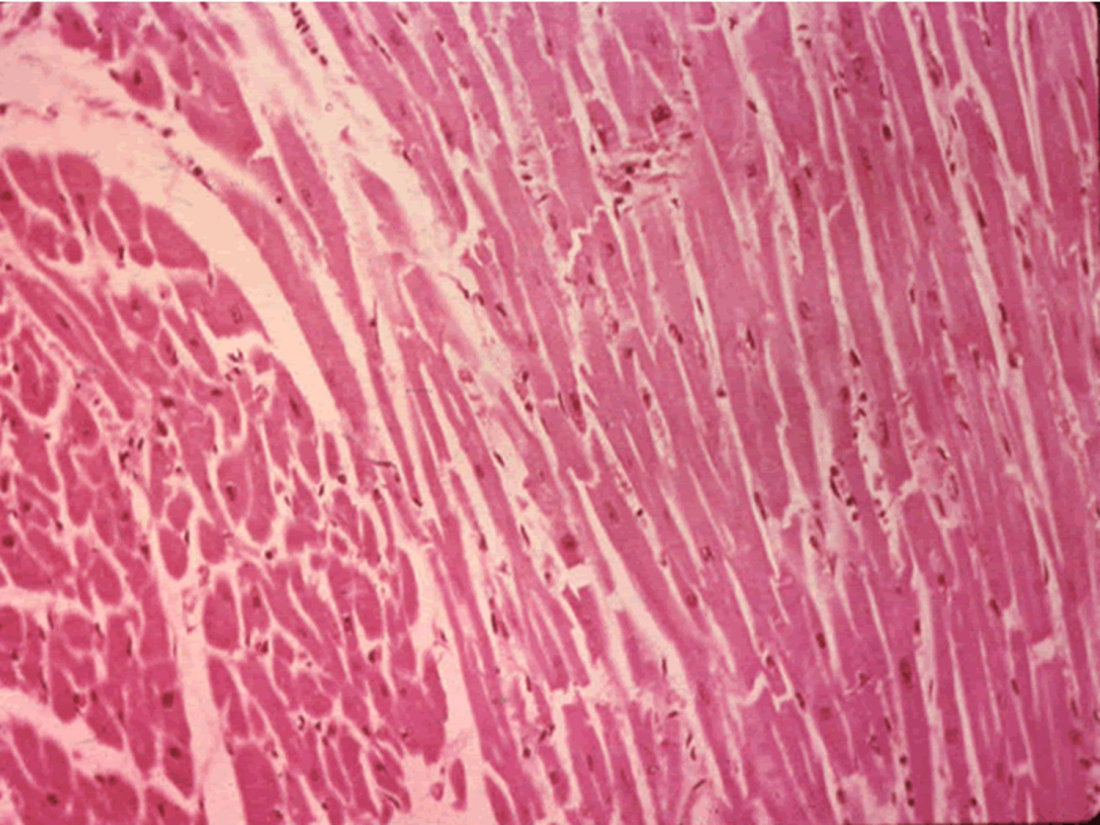

Half of the human body is made up of skeletal muscle which is capable of repairing itself in case of minor injuries. However severe trauma to the body as a result of accidents requires some sort of muscle regeneration which the body is often unable to provide on its own. This is where research like the mechanical stimulation of this specific process becomes relevant.

The method was tested upon two separate groups of mice. While one was provided with magnetized gel to be in direct contact with the damaged tissue, the other group was only given a robotic, pressurized cuff placed over the damaged part in a non-invasive manner.

The gel was exposed to magnetic pulses to bring about regular stimulation to the muscle. The robotic cuffs on the other hand were provided with pulses of air to regularly massage the required part. Over a period of two weeks, the results turned out to be markedly different.

There was a 2.5-times improvement in muscle regeneration and reduced tissue damage in the group which was provided mechanical stimulation. The reason behind this is that oxygen, fluids and important nutrients get transported to the injured regions as a result of direct stimulation and therefore help with muscle repair.

“This work clearly demonstrates that mechanical forces are as important biological regulators as chemicals and genes, and it shows the immense potential of developing mechanotherapies to treat injury and disease,” says Donald Ingber, a leading name in the field of mechanobiology.